How Cheap vs. Glamour seems to work

Glamour had a few very good years and cheap stocks lagged the market. As a consequence, voices calling “Value” dead become louder again. I don’t like calling it Value and Growth by the way, since cheap stocks can be worthless Value Traps and expensive stocks can be Value Stocks in the sense of growth at a reasonable price (GARP). Thus, I will call it Cheap vs. Expensive (or Glamour).

Cheap means that trailing multiples are low and positive, so (past) yield is high but - since the market is not totally clueless - this implies some sort of low future growth expectations.

On the other hand, Expensive or Glamour means that multiples are high and (past) yield is relatively low, however, the implied future growth rate of the company is high.

In a perfectly efficient market with a magic crystal ball, glamour stocks would deserve their higher trailing multiple due expected future growth which materializes and (in the sense of a DCF model) compensates for the lower starting yield. Cheap stocks would pay out dividends, buy back stocks and accumulate net cash at a high starting yield but lack growth. You can think about it from a high vs. low duration POV. In this perfect world, the baskets (including all potential bankruptcies and frauds) should have the same (risk-adjusted) return.

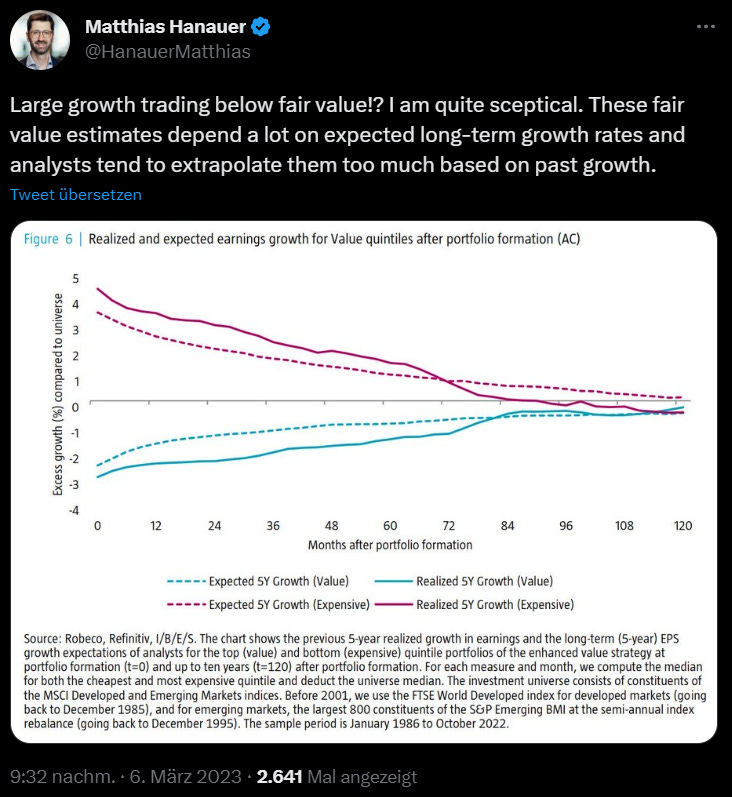

Unfortunately, we don’t live in this perfect world. Growth expectations by investors and analysts usually overshoot to the upside (downside) for glamour (cheap) stocks. As Matthias Hanauer stated:

Another important point is multiple expansion and compression within the baskets. As Jesse Livermore (not the real one) et al. at OSAM showed in this research, if you reinvest all distributions, you can boil down all returns of an equity portfolio to 2 basic components:

EPS Growth (revenue growth * margin changes)

Multiple Expansion

Since a Multiple Expansion is a “one-time” effect and long-term growth is compounding over the years, the “Neversell” crowd argues that you just need to avoid cyclicals and short-term trading and hold compounders forever. If you identify the Amazons of the world, this is a viable strategy. However, what people forget is that there is another way to grow EPS of your portfolio: Rotating into cheaper stocks ad each time getting more bang for your buck.

Here a table and chart from the article mentioned above:

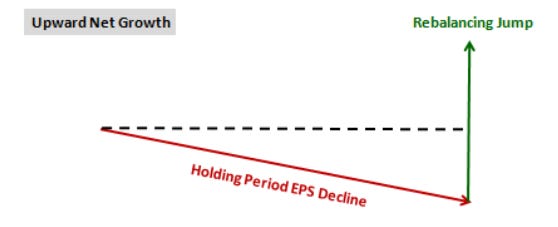

As we can see, the overall portfolio multiple expansion over the long-term was negligible (see last column) and the returns correlated well with the total portfolio EPS growth. The interesting part is the source of EPS growth. “Holding EPS growth” indeed was negative on average for “Value” (Cheap) and positive for “Glamour” (Expensive). So analysts and investors are right in their expectations directionally. However, by rotating into cheaper stocks each year, “Value” can overcompensate this negative EPS growth and even outpace “Glamour”. How so? For this, see the next two charts from the paper:

EPS of cheap stocks is expected to shrink or grow slowly, which on average is totally correct. However, if the expectations are low and the low growth is already priced in, price won’t (fully) follow EPS to the downside. As a consequence, multiples (Price/EPS) temporarily rise and at rebalancing, the investor can trade up into the next cheap stock. It sounds weird but that’s how a "low multiple” rotation strategy works.

So how can Value “die”?

Expectations and forcasts have to become better (more modest) to kill the possibility for overcompensation via rotation.

How would that look like?

We would most likely see a comparatively stable and low Valuation spread.

And where do we stand?

Well, Glamour outperformed over recent years but the Valuation spread widened back to dotcom bubble extremes:

As long as, we don’t see long-term “Cheap vs. Glamour” underperformance WITHOUT major valuation spread widening, I won’t accept any “Value is dead” talk. Glamour always had extended periods of strong multiple expansion which made Growth and Glamour investors look smart.

Excluding the Multiple Expansion

So the question arises: How would Cheap and Glamour look like if there were no such thing as multiple expansion in the baskets after rebalancing?

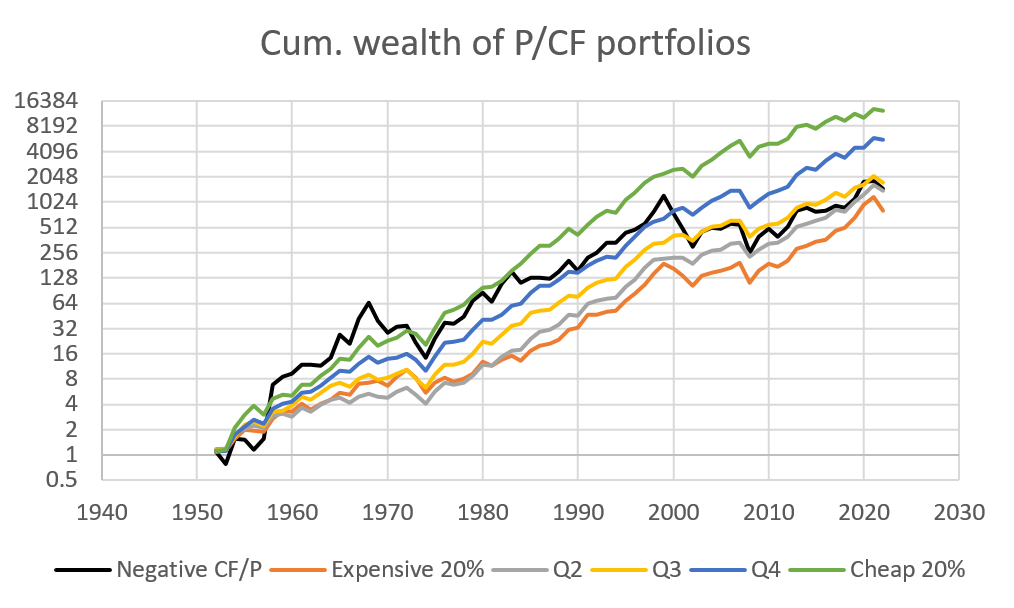

For this, I naively downloaded the FF CF/P sort portfolios and checked the annual data. Looking at the 5 Quintile baskets by P/CF + a basket of stocks with negative P/CF, these were the P/CF multiples over the years:

We instantly see that the multiples of more expensive baskets are more volatile. The negative P/CF basket naturally is the most chaotic one whereas rotation into the cheapest stocks has a multiple stabilizing effect. The median P/CFs in the timeframe were as follows:

If we check the performance of the vanilla baskets, the cumulative wealth charts look as follows:

We instantly notice that cheaper stocks outperformed over the long run. Interestingly, the negative P/CF basket - although quite volatile - even was the second best performer until 1999. From the slope of the “Expensive 20%” curve from 2009-2021, we directly see that Glamour had a good run recently.

Let’s now eliminate the time-dependent multiple expansion by multiplying the cum. wealth of each year with the term “(median P/CF) / (cur. P/CF)”. Since the 50s were rather cheap as a whole but non-profitable companies had a deeply negative multiple, the “start rerating” is rather rough in the given timeframe but evens out for CAGR. Unfortunately, with this method, calculating volatility or risk-adjusted returns makes no real sense especially for the non-profitable basket but that’s not so important now.

What this also shows me is that the common phrase “prices are more volatile than fundamentals” is not universally true. If markets would chase trailing multiples 1:1 at all times, there would be chaos in many stock prices. This seems to be at least one good thing about the existence of economists, analysts and forward PEs: They calm the market.

Here are the results:

Optically, there is not much change, except that the 2000-2009 period looks smoother for the most expensive stocks. This underlines the bubble formation affinity in these baskets and why you should be careful when running too many victory laps after a growth frenzy. To get a clearer picture: Let’s have a look at the CAGR:

As stated in the beginning, it is true that the impact of long-term multiple expansion on a portfolio basis becomes smaller the longer you invest. If we correct for P/CF expansion the 20% most expensive stocks (only) “overperformed” by roughly 1.1% per year. For non-profitable stocks, that number is at 1.7%. Since the valuation of the cheapest 20% and the next cheapest quintile (Q4) are near there long-term median, there is no major CAGR discrepancy.

So we see that the historically high valuation spread mainly comes from multiple expansion in expensive stocks. Cheap stocks are not cheaper than usual.

Let’s now supercharge the analysis by only looking at the postGFC data. Here you see the vanilla cum. wealth chart since 2010 but I added a hypothetical 2024 datapoint implying the re-rating of all portfolios to their respective long-term P/CF median by then (assuming no growth):

Basically, non-profitable companies would get killed in a re-rating without growth and most other portfolios including (the cheapest) would fall together. Interestingly, Q4 would perform best. This might be a hint that nowadays, cheap isn’t everything. As only portfolio, Q4 was able to back its performance by growth without multiple expansion. In my opinion, this is an argument for using a multi-factor approach and to look at quality, fundamental momentum and price momentum to avoid value traps, even if that means that you’ll skip a lot of the cheapest stocks.

Even though it’s very noisy in such a short time frame, see here the chart at stable multiples:

Here we see again that, on a fundamental basis, almost all baskets actually performed similar. So why did expensive stocks overperform and by how much:

It looks like there is a lot of danger from mean reversion to the expansive or non-profitable baskets. Unfortunately, as you see from the numbers: Cheap stocks aren’t really “supercharged” or something like that. They might just not suck as much. Nonetheless, they seem to be the best game in town. No one knows how long the growth frenzy will continue. The data I showed doesn’t even include the 2023 AI hype bull run. I personally look for pockets in “Cheap” with Momentum and Quality to avoid some of the Value Traps and to reduce opportunity cost. However, I will stay away from the over-extrapolated time bomb called “Glamour”.

It might grow into its multiple. It might be different this time. But I wouldn’t bet on it.

PS: I might repeat the exercise for P/E data since a big story over the past years was margin expansion. For this post, this would break the mold though.