Understanding Systematic Value/Momentum (Facts, Opinions and Fairy Tales)

I wanted to write a short piece trying to explain what happens in the background of my system, why I do what I do and what are the main differences between my approach and traditional value investing, deep value with a catalyst, GARP or a classic factor ETF.

Which factors do I use?

I basically have exposure to four well known factors: Size (SMB), Value (HML) and Momentum (WML) and Profitability/Quality (RMW or QMJ). However, these original factor definitions follow a rather academic construction, which tries to simplify the underlying effect down to one major metric, like Book-To-Market for HML (exception e.g. AQR’s Quality-Minus-Junk). In practice, it is wiser to not crown a “king of metrics” in a given category but to use Composites.

For Value I use a composite of P/B, P/E, EV/FCF, EV/EBIT, Shareholder Yield, P/OCF, P/S, etc. This approach was also described in Jim O’Shaughnessy’s “What Works on Wallstreet”. In this way, the system is much more robust against single outliers and accounting tricks. Furthermore, using a Value Composite gives to a lot of quality exposure and information between the lines (see next section). That is why I recently stopped using a separate quality rank in my system.

Similarly, I combine different lookbacks between 12 to 6 months for total return as well as an annual Sharpe Ratio and a regression-based slope to form a Momentum Composite.

For my usage of size, check the next section.

How do I use size?

Finally, I pay attention to size. I do not explicitly restrict the maximum market cap in my screening. Also all rankings on Value and Momentum are performed across all developed market stocks including large and megacaps. In most cases, the most extreme, cheapest, trending stocks in the universe are microcaps anyway. If a true largecap finds its way into the top of my ranking (a current example would be Stellantis), I skip it. The hypothesis is that factors lose a lot of explanatory power if the underlying security is broadly covered, liquid and part of many mutual funds, ETFs and indices, as the following chart shows:

It also becomes clear that the most juice is in the microcap space, which in the current definition of the database should cover everything below roughly $750 million marketcap. $50 to $500 million market cap is my preferred hunting ground but if I already own all accessible microcaps in the top 30ish of my screen and find a highly ranked smallcap (~ $750 - $2000 million) in the list, I consider adding it (a recent example was Höegh Autoliners). By the way, “accessible” means that I should be able to enter the position in one day (and it should be possible to exit the same way in the future) with a spread which can be justified over a holding period of 6-12 months. That usually means that if the bid-ask spread exceeds 5%, I’ll skip in almost all cases. My strategy is a low-conviction and mid-to-high turnover system and the expected return of each microcap name in the top 100 of my ranking is roughly the same without further information. So I simply can’t afford to burn 5-10% on spreads and there usually is no reason or benefit to it. A recent example of “buying too illiquid” was my buy of Paragon Technologies, Inc $PGNT (fortunately it was only a tiny starter position). It still sits in my book as a reminder, even though it doesn’t fit my criteria anymore.

Why did I stop using a quality composite?

Readers who know my portfolio updates on Twitter will remember that I also show quality ranks for my holdings. This quality composite is based on a rather broad mix of established quality metrics, including asset growth, a growth composite, gross margins, ROIC and FCF stability, debt, volatility, amongst others. If I would want to trade quality, especially in largecaps, I would do it exactly this way: Composites, composites, composites. However, as already mentioned previously, a Value Composite already contains a lot of information about the (current) quality of a business. Here some examples:

Using P/E, P/OCF, P/FCF, etc. == The company is currently profitable on different bases.

Using P/E and P/B or P/S (or similar) in combination == contains information about ROE or Net Margin (not negative, not too high with increased risk of mean reversion).

Using P/E and P/FCF or P/OCF in combination == contains information about accruals.

EV/EBIT == contains information about net debt relative to earnings (not overlevered, maybe even net cash).

Shareholder Yield == The company buys back stock and does not dilute shareholders.

In all these themes, especially debt, share issuance and profitability, excluding the worst offenders does 90% of the job, and that is already efficiently achieved by using a Value Composite. In this way a high rank in the Value Composite already gives you sufficient current quality. But what about future improvement of quality: For this we have the Momentum component. The nice thing about Momentum is that it does not care what the source or catalyst for improvement in sentiment, it just goes with the inertia-driven flow of the market.

No matter from which angle I tackled this topic, the conclusion for me boiled down to: In a concentrated Value-Momentum system, you don’t need a quality screen. More quality is not always better. You could even argue that you want quality to be as high as necessary to survive but as low as possible to leave room for improvement.

Don’t get me wrong, adding quality screens and especially volatility screens and smoothing profitability and value metrics over several years of data still will give you outperformance and that with lower overall volatility. However, most of the returns of Value and Momentum come from extreme, ugly, volatile businesses. Targeting a classic Value or Momentum factor but cherrypicking the pretty businesses is like driving with the handbrake on. Across literature and own backtests, I always found that limiting the universe to stable low-volatility businesses and sectors like consumer staples hurts Value+Momentum returns.

Am I worried about data quality?

The short answer: Not really. I stopped posting actual multiples from my screen when talking about single stocks on my Twitter because what usually happens is that three different people will cite three different numbers and sources on why my number is off by 10%. Data in microcaps can be messy. Different accounting practices, data providers which collect and update and clean the data according to their own procedure and that across continents and cultures… You will never get 100% of the truth.

However, imo it does not matter all that much in most cases. If you use relative ranks instead of absolute numbers, you already reduce the noise in your system. If you use composites on top knowing that any of the Value metrics also works in isolation, you additionally reduce the impact of any single point of failure in the data. And even if all the value data is 100% upside down and the cheapest stock in your screen is actually the most expensive stock in reality: This happening for multiple stocks in my portfolio is almost impossible. And for those stocks where it happens or (which is much more likely) where the given data is outdated, I still have momentum to fall back on which a) is fundamental-data-agnostic in itself and b) also works in isolation even in the crappiest stocks. Outdated value data if its at least younger than 12 months is no problem either most of the time. Ken French’s microcap value sort portfolios are reconstituted annually in June on lagged data and work just fine.

How do I implement the factors into one system?

I implement all my ranks in a long-only manner, meaning I am only exposed to the long legs of each factor. Also, I implement them in an integrated manner, meaning I buy equities which combine all the desired properties in one stock. The alternative would be a sleeve-approach (e.g. buying a pure Value portfolio with 50% of the capital and a pure Momentum portfolio with the other 50%). The integrated approach can be more volatile and definitely has lower capacity (which is why institutions and larger fund managers and ETF providers tend to prefer the sleeve methods imo) but it can boost returns in favorable market environments through interaction effects and larger factor concentration.

The universe currently contains over 18000 global stocks including Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and others. Russia and China are currently excluded due to geopolitical reasons (mainly confiscation risk) and not part of this number.

Composites are build by ranking the universe of stocks on single metrics, summing those up and reranking to the final Value and Momentum composite. For the final buy signal, I overweight the Value Composite, since its return/turnover is higher than that of the momentum signal (more about hit rate and turnover in a following section).

I track sector and country concentration. I rarely have to act on sector concentration but I have to cap country exposure, otherwise my portfolio currently would be 90% Japan and Poland. Currently, I try to target a 25% (nonUS) country cap. Current numbers:

How do I rebalance?

I usually don’t use backtests, as it increases the risk of overfitting and recency bias. However, imo backtesting can help a lot to understand the underlying trading mechanisms. So I used portfolio123 to backtest my strategy for the past 15 years and have a close look at the turnover and implied trading frictions/costs.

In a Value-centric factor system, most of the return comes from buying extremely cheap stocks (cheapest 1 or 2% on composite basis), and flipping them either because they have a huge run-up in price (good multiple expansion) or they have a bad quarter (bad multiple expansion). As a consequence, the tighter your rebalancing threshold for the overall ranking, the lower your hit rate and the higher your turnover but also the higher your return from riding the runners long and selling the losers quickly (especially with a momentum tilt).

So I tested how far I can go with my rebalancing band and a good compromise between return, cost and turnover (about 100% annually) was found for a 0.95 overall rank threshold. This is not a magical number, neither will it be of any use to you. Reducing the number will decrease turnover (and return) and increasing the number will introduce noise and costs. In the end, the transitions are rather fluent here, no reason to become too cute with the details.

To conclude: I screen and rank the data from my data provider quant-investing.com each Wednesday (arbitrary) and check if own of my holdings’ overall Multifactor Rank fell below 0.95. If not I do nothing. If it is the case, I replace it with a fresh top stock from the screen. Regarding the position sizing, I target about 3-4% per stock but let it float freely. I don’t rebalance actively to equal weight. Even if own of my stocks becomes a 6% position and another becomes a 2% positons, I am still a lot closer to the equal weight side on the Equalweight/Capweight spectrum.

What are the underlying trading mechanisms?

Most new investors which start out with quantitative value screens quickly burn their fingers and lose interest. “This does not work”. Imo, they just misunderstand the underlying trading mechanisms.

First of all, nowadays trying to invest into a large-cap pure value on your own, is hard and most likely a waste of time. There are a ton of Largecap Value ETFs out there, the space is flooded and most of the juice has most likely been squeezed. So, as a small DIY fish, you should look for food between the rocks, not in open water with the sharks. It is not hard to trade in and out of <$1000 million mcap stocks as retail investor but nearly impossible for institutions and ETF providers. So they have to compromise or they have to leave. Most ETFs are cap-weighted. As a consequence, nano and microcaps are naturally underrepresented. Furthermore, benchmark ETFs like IWC 0.00%↑ and IWM 0.00%↑ include all the junk and thus conceal the true potential of the microcap space.

But even if a retail investor decides to go into small and microcaps, she/he quickly faces obstacles if the underlying mechanisms are misunderstood. A concentrated Value and/or Momentum strategy lives from extremes and you should expect nothing less.:

Your screen will be full of shady steelmaking and shipping stocks, maybe in Poland or Italy. You will maybe see that the business lost money 3 out of 5 years and the stock price fell 80% over the past 10 years. Classic fallen angels. However, over the recent year, the stock rose 200% from its lows with multiple 30% corrections, now standing at a 3-year high and you just want to puke. You will also find a beauty here and there but they are too rare to fill the book.

So you swallow your pride, remember what all the quants told you about trusting the system and you buy a bunch of those ugly names from the top of your list. 3 months later most of them tanked and you become nervous. The momentum portion of your screen urges you to sell the losers and you listen. You buy a bunch of new ugly names which are optically cheap and at their 52-week high and they immediately tank, while some of the stocks you just sold rise 10% in value in a day. So you wait and a few months later, the system again urges you to sell the losers. Remembering what happened last time, you ignore the signal and hold. The stocks keep tanking and some of them fall 30… 40… 50… 60 %. After a few sleepless nights, you decide to quit.

I think this fictional story is close to the path many fresh DIY quant stock investing experience. People just see backtests like the following and don’t consider the implications:

With slippage (in theory), trading the top 5% of US/EU microcaps gave you about 20% CAGR with 50% drawdown. The exact numbers can vary strongly depending on market regime, so I would not anchor on this too much but these numbers also fit literature data. What is much more important imo: The hit rate is only about 50%!

People want strategies which only pick winners and which have no losing streak. But that’s not how the world works. Cutting losers fast and letting winners run in a tight system results in low win rates but (counterintuitively) also in higher returns. Every professional trader knows this concept (I recommend reading the “Market Wizards” books) but a layman investor often is shocked by it.

Going the route of selecting high-quality value compounders and holding them for years will dramatically increase your hit rate (and comfort) and is a totally legitimate strategy. Just understand, that those are two totally different games. The problem with higher holding periods is that predicting the future over several years is hard and identifying the rare long-term winners is like searching the needle in the haystack. Higher-Turnover value/momentum strategies make lower-quality companies with quasi zero terminal value investable through frequent reevaluation.

You WILL buy a lot of Value Traps.

You WILL buy a lot of losers.

You WILL buy a lot of companies nobody has ever heard of and nobody cares about.

Basically all the returns will come from a handful of big winning trades. All the small wins are just to offset the losses (which where limited in time).

Slight Momentum tilts can help you to ride winners longer and cut losers earlier (in return for a higher turnover). Hypothetical value for my system (as of today) over the past 15 years:

Unfortunately, I traded a lot looser rebalancing bands (0.8 threshold) including quality screens until recently. My returns thus are much closer to a vanilla developed markets microcap momentum benchmark (~17% CAGR since 2019/05). More would have been possible especially in 2022/23 with a tighter approach.

What are the main differences to other classic Value strategies or Factor ETFs?

ETFs

Most Factor ETFs are sleeve single-factor (no direct combination of value and momentum), contain a lot of stocks, are cap-weighted and have slow rebalancing schedules with wide bands. As a consequence, most of them don’t move the needle and have low factor loads. However, especially in the small-cap universe, there are some good alternatives. Closest to my approach would be $XSVM. For microcaps Value, also DEEP 0.00%↑ is nice (no momentum exposure though). In Europe, the best alternatives are $ZPRV and $ZPRX in my opinion (also no momentum exposure). However, a big blind spot is always the intersection between micro, value, momentum, global, concentration and tight rebalancing and I doubt it will ever be viable for an ETF. The capacity is just too low. The main edge of a retail investor is that he does not have to care about capacity.

GARP/BUFFETT

Those strategies basically take the approach of “everything which trades below its intrinsic value is value” and target longer holding periods for finding quality compounders. In a “Current Multiple” vs. “Future Growth+Quality” diagram, they would try to go as far a possible into the Cheap/HighG+Q quadrant. My approach and similar quant Value approaches don’t care about the G+Q axis directly. Extreme cheapness is priority number one. Without the momentum component thus you basically enter deep value or “cigar butt” territory. By adding momentum, you now basically enter a sentiment component, however, you do not care what is the recent for this change in sentiment. It can be growth, it can be a new source of revenue, it can be a turnaround or a macro narrative, etc. The only thing that matters is that a previously hated asset is now less hated and that inertia in the market is high enough to keep the trend moving.

ANTICYCLICAL VALUE

As a consequence, I think it is a misconception to think of the strategy as anticyclical, even without the momentum component. If you include P/E and similar metrics into the strategy, the base case for a stock to buy is that is was recently earning a lot of money and the market thinks that this is not sustainable. You bet against the market in this regard by assuming a continuation of good quarters and a resulting multiple expansion. You are the actually the procyclical investor in this scenario! Add momentum and you underpin this concept by waiting for confirmation of more and more market participants thinking the same.

DEEP VALUE WITH A CATALYST

A discretionary concept which is really close to my strategy but also very different from it, is buying deep value with a catalyst. As described earlier, the “catalyst” in my approach is hidden in momentum. In this regard, it does not matter if insiders and niche experts see something in the business which is not public yet or if the momentum originates from more and more market participants catching on to a public narrative. The “Value” component delivers the fuel, and the “Momentum” component delivers the activation energy. Discretionary investors looking for explicit catalysts do something similar. The advantage here is that non-quantifiable aspects can be included (such as management changes, new potential products, activist actions, etc.) which don’t show up in the performance (yet). Also especially ugly Deep Value stocks “which don’t screen well” e.g. from the biotech space can be identified.

What is my current portfolio?

Here it is.

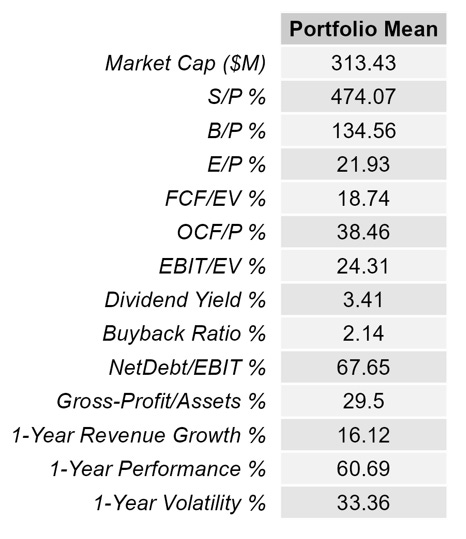

Here are the average portfolio metrics:

Cheers!

Super Artikel, danke! Ich arbeite viel mit den Seeking Alpha Quant Ratings. Da mir die historischen Daten nicht zur Verfügung stehen, kann ich leider keinen Backtest machen, aber ein Jahr Paperaccount hat mich doch wirklich überrascht - mit einem Stump-ist-Trumpf-Ansatz hätte ich 80% p.a. gemacht.

Hast Du Dir die SA Quant Ratings schon mal angeschaut, und was hältst Du davon?

Awesome article, thank you. I'd love to do this with a portion of my money but don't have the technical skills. Appreciate you sharing your favourite listed alternatives and hope you do even better fishing where the big guys cannot. Cheers